Outrage as Slovak MVNO Okay Fon Launches Roaming but Faces eSIM Meltdown

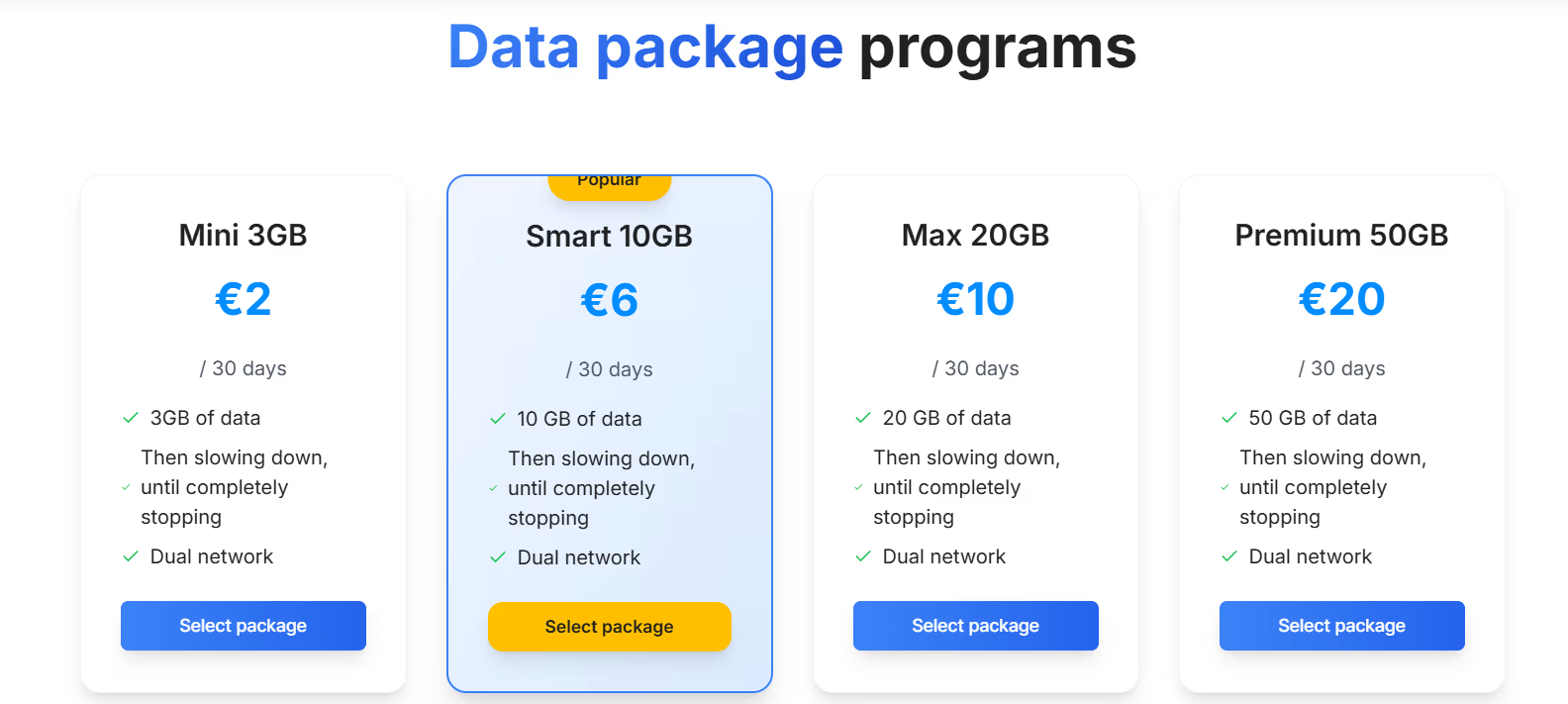

Slovakia‘s mobile market is getting a new player – Okay fón, a new mobile virtual network operator (#MVNO), has officially launched in the country. The company, founded by Štefan Ďurina, operates exclusively online, offering only eSIMs with no physical stores. At launch, Okay fón is a data-only provider, meaning calls and SMS/MMS aren’t included, and all services are contract-free. Customers receive their eSIM via email after purchase and can activate it instantly.

One of its standout features is the ability to connect to two Slovak networks (Orange and O2). Users can either manually switch or let Okay fón’s smart switching algorithm handle it. The system checks signal strength every 30 seconds and automatically switches to the stronger network—without interrupting the data session. The MVNO has entered the market with four data packages, which, according to Ďurina, are competitively priced and “won’t get worse” over time.

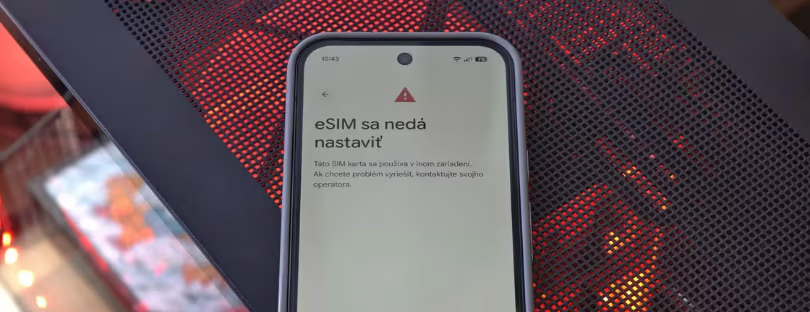

Yet within days, excitement gave way to frustration. Instead of cementing trust, Okay Fon’s launch was overshadowed by a critical failure: its eSIM services collapsed entirely, leaving customers without connectivity. What should have been a milestone turned into a reputational crisis.

eSIM Outage Sparks Customer Outrage

Shortly after the roaming launch, all eSIMs issued by Okay Fon stopped working. Customers who had embraced digital SIMs for fast setup and travel convenience suddenly found themselves stranded without service. For those abroad, the timing could not have been worse.

Reports of outrage quickly surfaced, with users demanding explanations and immediate fixes. Okay Fon has acknowledged the disruption but has not yet provided a clear reason for the failure or a timeline for restoration.

Why MVNOs Struggle with eSIM

Okay Fon is not alone in these difficulties. Across Europe, MVNOs eager to appear innovative often rush to adopt eSIM without fully preparing their systems. The challenges include:

- Complex provisioning platforms that require flawless integration between the MVNO and its host operator.

- Dependence on external vendors for eSIM management, which can magnify small errors into large-scale failures.

- Insufficient fallback options, meaning a single fault can disable service for the entire eSIM user base.

Other operators in Spain, Germany, and the UK have faced similar headaches—sometimes pulling their eSIM offerings entirely until stability could be guaranteed.

Impact on Customers Abroad

For Okay Fon subscribers, especially those traveling in the EU, the outage is more than a technical glitch. It leaves them unable to rely on their phones for navigation, communication, or business. Some have been forced to buy emergency local SIMs or turn to global eSIM providers just to stay connected.

Short-term advice for customers includes:

- Requesting a physical SIM replacement as a backup.

- Exploring alternative eSIM providers for travel needs.

- Monitoring Okay Fon’s official updates for compensation or service credits.

A Wider Market Parallel

The Okay Fon episode reflects a bigger truth: the eSIM transition is reshaping telecoms, but not all players are equally prepared. Larger carriers have invested heavily in infrastructure and redundancy, ensuring smoother rollouts. MVNOs, constrained by tighter margins and reliance on wholesale agreements, often lack the same resilience.

The pressure to adopt eSIM is intensifying, particularly since Apple introduced eSIM-only iPhones in the US. This decision effectively forces operators worldwide to support the technology, whether or not their backend systems are mature enough. The risk is clear—move too slowly and you appear outdated; move too quickly and you risk outages like Okay Fon’s.

Expert Conclusion

Okay Fon’s launch of EU roaming should have been a turning point, elevating its brand within Slovakia and attracting frequent travelers across the region. Instead, the simultaneous collapse of its eSIM services has triggered outrage and eroded customer trust.

From an expert perspective, this is emblematic of the double-edged nature of eSIM adoption. On one side, it offers streamlined onboarding, reduced distribution costs, and a future-proof image. On the other, it exposes MVNOs to technical vulnerabilities that, if mishandled, can damage reputations overnight.

For MVNOs across Europe, the lesson is clear: success with eSIM depends not on speed, but on stability. Robust provisioning systems, transparent communication during crises, and contingency planning will separate winners from those left behind. Okay Fon’s stumble is a cautionary tale—one that illustrates both the promise and the pitfalls of going digital-first in today’s telecom market.