Study Exposes How Travel eSIMs Reroute Data Through China — and Let Anyone Become a Reseller

A growing number of travel eSIM providers are quietly routing user data through networks in China and other unexpected countries, exposing travelers to surveillance and jurisdictional risks, according to a new academic study.

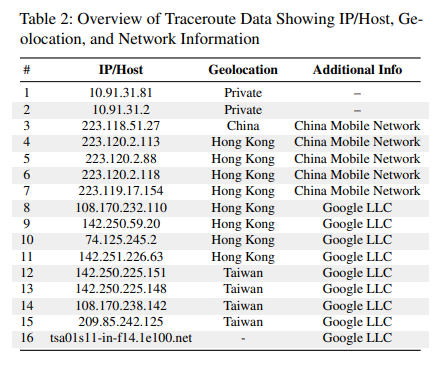

Maryam Motallebighomi, Jason Veara, Evangelos Bitsikas, and Aanjhan Ranganathan, researchers from Northeastern University, examined 25 popular eSIM services, including Airalo, AIRSIMe, Alosim, Better Roaming, BNESIM, BreatheSIM, CMLink eSIM, DENT, eSIM Access, Eskimo, Flexiroam, GigSky, Google Fi, Holafly, Maya Mobile, MTX Connect, Nomad, Numero eSIM, RedTeaGo, Saily, T-Mobile, Ubigi, USIMS, Voye, and Yesim and found that many profiles rerouted traffic through infrastructure outside the user’s destination — with Chinese carriers appearing disproportionately often. In some cases, users in Europe saw their traffic exit in Asia before reaching the internet, with no disclosure from the providers.

“The destination IP address and the user’s physical location often don’t match, which means data is being routed through third-party countries without travelers’ knowledge,”

the researchers said. “That raises concerns about privacy, lawful interception, and compliance with local data protection laws.”

Their analysis, presented at the 34th USENIX Security Symposium in Seattle, United States, pointed to a pattern of opaque routing arrangements with eSIM provider networks.

Security Concerns Beyond Routing

Security Concerns Beyond Routing

The revelations come amid broader scrutiny of eSIM security. In July 2025, security firm Security Explorations disclosed a vulnerability in Kigen’s eUICC, used in billions of devices worldwide. The flaw allowed malicious profiles to install unauthorized applets, a risk since patched under new GSMA standards.

Separately, researchers in Poland demonstrated how cloned eSIM profiles could silently hijack a subscriber’s identity — intercepting messages and calls in real time. These findings highlight how eSIMs, despite being marketed as safer than physical SIMs, are not immune to exploitation.

Rising eSIM Fraud Cases

Fraud linked to eSIM technology is also increasing. In the UK, reports of SIM-swap attacks—where criminals trick carriers into transferring a victim’s number to a rogue eSIM—surged from under 300 in 2023 to nearly 3,000 in 2024. Losses have exceeded £5 million, according to The Times. Elderly users were among the most frequent victims.

Silent and Proactive eSIM Behavior Raises Red Flags

One of the more unsettling findings from the Northeastern study was that certain eSIM profiles engaged in silent, proactive behavior without any user action. For example, when researchers installed an eSIM Access profile, the device immediately initiated a background connection to a server in Singapore—even before the user placed a call or browsed the internet. Similarly, a Holafly profile triggered the retrieval of an SMS from a Hong Kong number automatically, without the user requesting or authorizing any messaging activity.

Would you like me to also connect this to user risks (e.g., extra roaming charges, privacy breaches, spoofed SMS trust issues), so the section feels more practical and less purely technical?

Lack of Transparency

What worries experts most is opacity. Many eSIM providers fail to disclose where traffic is routed, making it nearly impossible for customers to assess the risks.

“Consumers assume their data flows locally, but in reality, it can pass through jurisdictions with very different surveillance laws,”

said telecom analyst Patrick Donegan.

Some providers defend the practice as a technical necessity, citing roaming agreements and cost efficiency. But privacy advocates argue that undisclosed routing undermines user trust and could contravene GDPR and other regional privacy frameworks.

A Shockingly Low Barrier to Become an eSIM Reseller

The Northeastern researchers also uncovered how effortless it is to set up as an eSIM reseller, raising alarms about oversight and user safety. By registering with platforms like eSIMaccess and Telnyx, they were able to launch their own eSIM shop armed with little more than a valid email address and a payment method. Despite the minimal entry requirements, resellers gained deep access to sensitive subscriber data, including IMSI numbers, device identifiers, and even location information accurate to within 800 meters. In Telnyx’s case, the platform also allowed resellers to send SMS messages directly to users. The finding highlights a glaring regulatory gap: while traditional MVNOs face stringent compliance and auditing, eSIM reselling can be done almost instantly by virtually anyone, leaving customers exposed to risks they may not even realize exist.

What Travelers Can Do

Experts recommend that travelers:

- Choose providers that disclose routing and data residency policies.

- Enable strong authentication on carrier accounts to reduce fraud risks.

- Use a trusted VPN when handling sensitive communications abroad.

- Update devices to patch known eSIM vulnerabilities.

As global eSIM adoption accelerates—GSMA projects 7 billion active eSIM devices by 2030—transparency and accountability around routing will be critical. Until then, experts warn, travelers may be unknowingly handing their data to foreign networks.

What Silent eSIM Behavior Really Means for You:

1. Loss of visibility and control

When an eSIM profile silently connects to servers (like eSIM Access reaching Singapore) or retrieves SMS without your action (like Holafly pulling one from Hong Kong), you don’t know what data is leaving your phone or why. For a traveler, that means your traffic may already be exposed before you even open a browser.

2. Exposure to surveillance and interception

If the silent connection happens through networks in China, Hong Kong, or other jurisdictions with broad surveillance powers, your device could be subject to monitoring outside the legal protections of the country you’re physically in. That’s a real privacy and security risk.

3. Data leakage and profiling

Background connections can reveal your device identifiers, IMSI, and rough location — enough to build a user profile or track movements. This is especially concerning when resellers (with very low entry barriers) have access to those data feeds.

4. Potential fraud vector

Silent SMS retrieval is particularly risky because SMS is still widely used for banking and two-factor authentication. If a profile can fetch SMS in the background, a compromised reseller platform or malicious actor could abuse that channel.

5. Hidden costs for travelers

Even if nothing malicious happens, background traffic routed through unexpected networks can trigger unintended roaming charges or consume prepaid data without your knowledge — a practical pain point for budget-conscious travelers.

👉 Bottom line: For an everyday traveler, this isn’t just a technical quirk — it’s a mix of privacy risk, fraud exposure, and hidden cost. It means your “convenient travel eSIM” might act more like a silent operator you never agreed to, deciding where your data goes and what background services run.

Alertify conclusion: the winners will be the eSIM players that make routing transparent—and controllable

Alertify conclusion: the winners will be the eSIM players that make routing transparent—and controllable

The Northeastern/USENIX work doesn’t just flag a bug; it exposes a structural truth about travel eSIMs-as-marketplaces: many rely on centralized breakouts and sponsor networks that may exit traffic far from the user. By contrast, providers with their own core and distributed points of presence (e.g., 1GLOBAL, ex-Truphone) tend to keep tighter control of routing paths and publish a single APN across footprints—signals of a more “operator-grade” approach. That difference is material for privacy, latency, and regulatory exposure.

Among the aggregators, architecture choices vary. Independent network measurements (arXiv, 2025) found Airalo’s ecosystem shows home-routed traffic for some plans breaking out through Singtel PGWs in Singapore—consistent with IPX/GRX centralization—while other travel brands behave similarly but disclose little. This is convenient for scaling SKUs globally, but it creates the exact opacity the study highlights. If an aggregator won’t tell customers where packets exit, assume centralized routing and act accordingly. arXiv

The market is already pivoting. Transatel/Ubigi has rolled out a “Country of Residence IP” toggle that lets users choose a home-country IP or a regional IP natively at the eSIM level—essentially a lightweight, operator-side exit-node selector. Expect this to become table stakes for travel eSIMs that want enterprise and privacy-sensitive users: give customers visibility (where does my traffic exit?) and control (can I change it?).

Security pressure will accelerate that shift. The 2025 Kigen/eUICC test-profile issue—and GSMA’s rapid hardening in TS.48 v7.0—underline that eSIM trust now depends on verifiable practices, not marketing. Players that publish security advisories, track standards changes, and prove patch cadence will differentiate; those that stay silent will be treated as high-risk, especially by corporate buyers.

Macro-trend: adoption keeps climbing toward ~6–7B eSIM smartphone connections by 2030, so scrutiny will only intensify. The competitive edge will go to providers that (1) document routing and lawful-intercept jurisdictions in plain language, (2) offer selectable/local breakout where possible, and (3) certify against the latest GSMA profiles with publish-prove transparency. In short: the “best” travel eSIM in 2025 isn’t the cheapest per GB—it’s the one that shows its homework on where your data actually goes.

Security Concerns Beyond Routing

Security Concerns Beyond Routing